The Gold of Monte Rosa and Its History

Thanks to state-of-the-art technology, one of the most important gold finds of the 21st century was made in the Alpine region. About a treasure hunt where the truth prevailed in the end.

Table of Contents

Mining on the Monte Rosa

The gold deposits of Monte Rosa extend over a large area along the eastern side of this mountain range. The gold-bearing trains consist mainly of quartz, to which calcite and magnesia-rich carbonates are added.

carbonates, which are the result of the transformation of the ore minerals. These are mostly individual inclusions, which can reach massive concentrations in some places.

Gold mining in the valleys of the Italian Aosta Valley must be very old. In one place at the entrance to the Aosta Valley, called Bessa, the ancient Romans unearthed an incredible 200,000 kilograms of gold. The famous Roman naturalist Pliny calculated this. According to regulations, five thousand slaves were allowed to work for the Roman masters. An ideal number. If a few were missing, the yield would not have been so productive. A few too many and the Romans might have been beaten to death by the rioting slave rabble. The ancient Romans managed to wash all the gold out of the rubble in less than a century. That's why not a single crumb can be found in the Bessa today.

We also had no intention of dealing with crumbs. In the Val d'Ayas in particular, some old galleries were discovered in the middle of the 18th century. One of them, in Bouchej, contained a myriad of outstanding gold specimens on rock crystal, so much so that it went down in history. However, myths have always been in the foreground. They tell of a miner who once discovered a special gold nugget. As he was sure he would be searched by the miners, he made a deep wound in his thigh. He hid the gold in it, as much as it hurt like hell. He really did manage to smuggle the treasure out of the mine. But the truth came to light. As punishment, they chopped off his foot and nailed it to the entrance of the mine as a warning.

In 1842, four hundred workers were already employed in the Anzasca, Toppa and Antrona valleys, extracting 194 kg of gold. However, the yield from the mines fluctuated from year to year. The particularly gold-rich veins were therefore called "spade", "swords", by the miners, as they appeared in the form of elongated lenses. They were the object of everyone's hope and search: a single "sword" could sometimes contain up to 40 kg of gold.

In 1898, the Swiss company "Société des Mines d'Or de l'Evançon" was founded in Geneva. Among other things, it promised gullible shareholders that there were heaps of gold on the Ciamousira mountain east of Brusson, near the hamlet of La Croix. A gamble! However, the Swiss were soon at the end of their tether. But in the meantime, the confidence of other investors had been aroused by the English "The Evançon Gold Mining Company Ltd" in 1902. "SPERANZA" the "HOPE" was the name they gave to a new tunnel section branching off from the Fenillaz vein in the middle of the mountain. Five hundred miners drilled seven access tunnels for the English company. They called them "Livelli". In between, they hollowed out the rocks and excavated the quartz veins, which were up to two meters thick, over a length of 2,500 meters. In 1910, the mines were closed "after the rich fenilla vein had been extracted to about two thirds.

The treasure map of Dr. Reinhold

Immediately afterwards, the Swiss mineralogy professor Carl Schmidt commissioned the young Dutch student Thomas Reinhold to write a dissertation on „Die Goldpyritgänge von Brusson in Piemont“ (The gold pyrite veins of Brusson in Piedmont) and made all his documents, as well as those of the now liquidated gold company, available to him.

Reinhold did this meticulously and completed the work on March 8, 1916, writing: "The gold is found almost exclusively as free gold. At first glance, the gold finds appear to be irregularly distributed in patches throughout the entire vein." And further "The gold enrichments described here can be very considerable and in rare cases have a local extent of several cubic meters. For example, on May 29, 1908, 40 kg of gold was found in 462 kg of vein mass at the upper end of gallery No. 4, 185-187 m from the mouth, approximately in the middle of the mine. A neighboring ore nest of 244 kg vein mass contained 28 kg of gold. In February 1909, a gold-rich zone of 58 kg of quartz with 3 kg of free gold was found between adits 4 and 5."

And as if that wasn't enough, the meticulous student drew in the individual large gold finds of the past like a treasure map. With a description of his mineralogical knowledge, "... that the richest gold sites were mainly found where the vein intersects the mica schist near the limestone." And he ended "The total yield of ore in the years 1904 - 1909 amounts to ... 716,953 kg of gold."

The lure of gold

We concluded that there must be at least 300 kg of gold in these tunnels. And there were no detectors around 1900. We - the twins Mario and Lino Pallaoro, Federico Morelli from the Italian province of Trentino, Georg Kandutsch and Michael Wachtler - set off. But not with much hope. Gold in such quantities can't just be there for the taking! We took the thin booklet with us, along with the gold finds marked in it. We lit the carbide lamps, crossed the rusty gate and waded knee-deep in the cold water. In a side tunnel, we heard the sounds of the last gold prospector, Florindo Bitossi. He had been mining the rock with old-fashioned machines for decades. A few crumbs of gold were sometimes his reward. His body was as emaciated as the rock. He was to die in 2006.

Then we stood at the point where once, in the distant year 1908, an incredible 68 kg of pure gold had been found. In our minds we imagined the crowd, the cheers of the miners, who nevertheless didn't get a cent more pay because of it. And who ultimately didn't care how this gold got here or how it was produced.

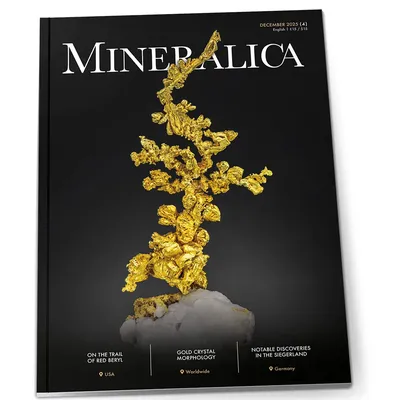

Then we pulled the latest generation of metal detectors out of our rucksacks. Thousands of sparkling rock crystals in all variations, from small to large, lay in piles in the heaps. We noticed them at first. Then we didn't. The detector struck. First in the slag heap. Previous miners had probably blasted down a piece of rock and not searched the overburden carefully enough. Piece after piece of gold came out. Like works of art from nature.

Sometimes rock crystals grew out of the pure yellow precious metal, then again it crystallized into the most beautiful shapes. "What if the mountain suddenly collapsed!" The very thought was frightening. No one would find us.

We worked in a frenzy and still didn't notice any progress in the cold and darkness. Late in the evening, we looked for a place to stay in the tourist town of Brusson. We talked a lot over beer and wine. The next morning we were back in the mine of "hope", the "Speranza". The blocks got bigger and bigger and gold sparkled everywhere.

The new premium magazine for mineral collectors

4 issues per year – packed with fascinating finds, expert knowledge, and collector passion. The first bilingual magazine (German/English), including full online access.

Explore subscriptionThe End

"Silence or speak" was the most important issue for us. Because: "Gold never belongs to the one who finds it". We decided to tell the story. We exhibited the finds at the Mineral Days in Munich and thousands of people were amazed that such a thing was even possible in modern times. Our possessive instinct was not particularly pronounced. And why should we: just to bury the gold in our own garden, we could have left it in the mine. The police and the public prosecutor's office got involved. The gold was measured, weighed and estimated. It is said to have been 30 kg in total. Everyone took their own pieces. The museums in Valle d'Aosta, Piedmont and Milan. Something always stayed with us: the story! Quite apart from that: Did we really do it for the money? Or because of the adventure and the knowledge of being free people?

In 2015, they then opened the "Museo dell'Oro" with a great deal of architectural boldness, right on the spot where we made the finds. They told the story of the once glorious gold mining. They sealed the rocks so that no one would even come close to finding more gold crumbs. But we had no intention of doing that. We were drawn to new shores and discoveries. In the knowledge that we had found something great.