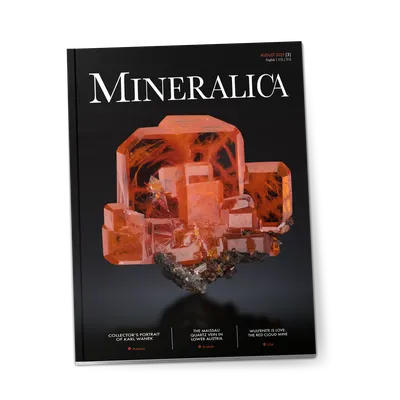

Wolf Mine: A Famous Locality For Rhodochrosite

The Wolf mine in Siegerland in Germany has had a long and eventful history. Although the Siegerland region is known for its iron mining, the Wolf mine stands out in particular for its colorful minerals. First and foremost is rhodochrosite, which the miners used to call “raspberry spar”.

A “late bloomer” with an ever-changing history

When studying the historical publications on Siegerland minerals from the 18th and 19th centuries, it is remarkable that rhodochrosite from the Wolf Mine is not mentioned anywhere. Although the equally beautiful rhodochrosite finds from other Siegerland mines such as Ohliger Zug, Frauenberger Einigkeit and Louise are mentioned, there are no references to the magnificent crystal specimens from Wolf Mine, which are now found in collections around the world. It was not until 1912 that Rudolf Nostiz provided the first detailed description.

The late description of Wolf Mine is because it was a bit of a “late bloomer” among the Siegerland mines, the names of some of which are known since the late Middle Ages. The iron ore veins in the area south-east of Herdorf had probably been known for a long time but it was not until 1834 that the deposits began to be developed via a small adit. This was, however, apparently without lasting success, because in 1885, Alfred Ribbentrop's description of the Daaden- Kirchen mining district only lists the mine as an entry on the mine register. This suggests that no extensive mining work had taken place here up to that point. This was soon to change: as early as 1890, work began to investigate the deposit at greater depths using a machine shaft. The results were apparently so promising that the mine was further expanded in the following years.

In 1917, the Essen-based Krupp company, who already owned numerous other Siegerland mines at the time, acquired the Herdorf mine and continued to expand the facilities. Despite quite good production, the declining economy after World War I forced the operators to cease operations in 1925. It was not until 1937, shortly before the start of World War II, that Wolf Mine was reopened and in stable production until 1945, when the effects of the war led to the next shutdown.

In about 1953-54 the lights were turned on again – this time, though, combined with the neighboring San Fernando Mine, which had also ceased activity towards the end of the war. The two mines were connected underground and the San Fernando shaft now served as the main hauling shaft. With a workforce of up to 670 miners, daily production was around 750 tons of ore. The operation was permanently shut down in 1962 as the exploitable ore reserves had been exhausted and the operation became unprofitable. In the end, the combined San Fernando-Wolf Mine reached a total depth of 930 m.

Prior to the connection to San Fernando Mine, the Wolf Mine had produced around 1.25 million tons of iron ore; the total output of San Fernando Mine is estimated at around 6 million tons of ore. For a decade, the Wolf Mine’s headframe sat like a throne on the ridge above the Heller valley and was considered one of the last landmarks of the Siegerland mining industry, which completely disappeared in the 1960s. However, due to acute dilapidation, this symbol of the 2,500-year Siegerland mining tradition also fell victim to demolition in 1975. Today, an industrial area covers the site of the former Wolf Mine and only the magnificent specimens remain as a reminder of what was once a very important mine.

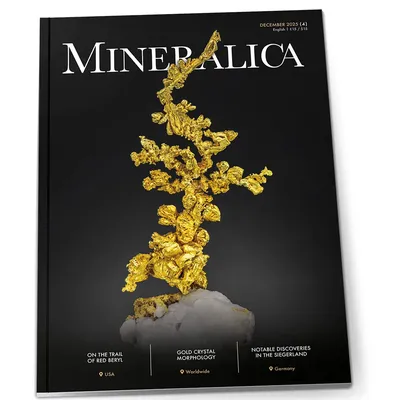

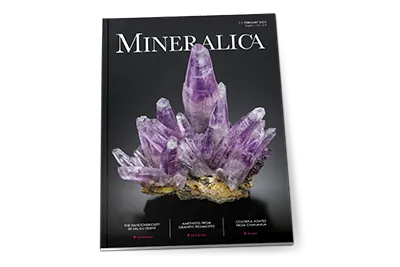

The new premium magazine for mineral collectors

4 issues per year – packed with fascinating finds, expert knowledge, and collector passion. The first bilingual magazine (German/English), including full online access.

Explore subscriptionSiderite veins with lead, zinc, copper and nickel ores

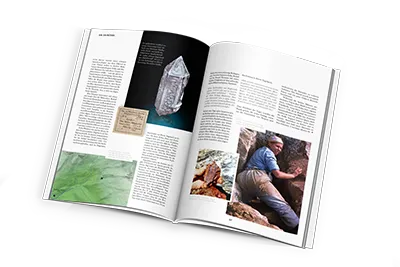

The up to 7 meter-thick siderite veins of Wolf Mine formed the northern end of the so-called “Florz-Füsseberger lode tract”, a thick formation around 4.5 kilometers long, striking north-south. In addition to the Wolf and San Fernando mines, other important mines, such as Friedrich-Wilhelm near Herdorf and Füsseberg near Daaden, which are also well-known to collectors, also exploited this lode tract. The primary ore of the deposit consisted of siderite, which was in some place more, in others less interspersed with quartz. Adolf Hoffmann noted in 1964 that the vein in the area around Wolf Mine was probably quite poor in cavities, which is why remarkable finds of crystallized primary ore minerals were rare. The most interesting primary mineral of Wolf Mine for mineral collectors is probably millerite, which was found in 1955 on the 520 m level in sheaf-like aggregates or in nests of unoriented needles up to 1 cm long.

Quartz, galena, sphalerite, pyrite or chalcopyrite crystals were also found, mostly sitting on a bed of very small bladed siderite. Ullmannite is a rarity that occurred on the 500 m level as idiomorphic crystals and aggregates enclosed in siderite (cf. Bode 1980). All in all, these minerals are known of better quality from other Siegerland mines.

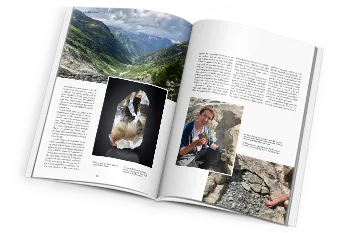

A raspberry-red splendor: The rhodochrosite of Wolf Mine

The particularly deep oxidation zone in the area around Wolf Mine is unusual. Down to the 400 m level, the siderite was completely or largely transformed into brown iron ore (limonite). This was and still is a stroke of luck for mineral collectors, as great specimens with rhodochrosite and other minerals have been found in this area. Former miners reported how countless red rhodochrosite crystals sparkled in the light of their lamps, sometimes in druses more than 1 m in size. One can only begin to imagine what a magnificent sight that must have been. The best finds were made between the 300 and 350 m levels, in the transition zone between the secondary brown iron ore and the primary siderite. The nearby siderite provided the necessary carbonate environment and the manganese content of aqueous solutions, creating ideal conditions for the formation of the manganese carbonate rhodochrosite. Rhodochrosite was referred to as “raspberry spar” by earlier miners. Even today, this term is often used, partly because of the raspberry-red color of the mineral, but also because of the occasional raspberry-like formation. Raspberry to rose-red scalenohedral crystals, which can reach a length of up to 2 cm, are typical for Wolf Mine. Smaller crystals look almost like grains of rice.

To be precise, the larger scalenohedra in particular are not single crystals at all, but rather a close sub-papallel intergrowth of numerous individuals, which can be observed on closer inspection or at least in SEM-BSE images. These crystals or aggregates line the cavities in the matrix of brown, sometimes ochre-yellow limonite and quartz like a lawn or unite to form small groups, sometimes crossing each other and forming wonderful rosettes - like bright red flowers sitting on a deep black background of goethite “kidney ore”. Other exquisite specimens show stalactitic habits, which are made up of numerous individual crystals or radiating, botryoidal to reniform aggregates.

Variations in calcium and/or magnesium content can cause the color of rhodochrosite to drift into pale red or light pink tones, while higher iron impurity results in a more yellowish-brown color. To this day, the deep red, beautifully crystallized and richly studded specimens are particularly sought-after by collectors worldwide and are a classic that is traded at high prices on the mineral market. Rhodochrosites from Wolf Mine are unlikely to be missing from any renowned collection of classic European minerals.

The must-have for everyone who collects minerals

Mineralica is your premium collector’s magazine – made exclusively for lovers of minerals and fossils. In print, bilingual, and with full access to the complete online library.

View issue previewCopper, cuprite and other remarkable mineral finds

Other minerals are also widespread in collections. Foremost among these is native copper, which is also one of the most common associates with rhodochrosite. The copper usually forms simple small flakes and tablets, which are usually around 2 to 3 mm in size and rarely reach around 1 cm. In the vast majority of cases, the copper is coated by a thin patina of malachite, more rarely by brochantite (slightly darker green), which in combination with the red manganese carbonate provides a special splash of color. In addition, particularly beautiful, dendritic, branched or fern-like aggregates of native copper have also been found. These also occur without rhodochrosite in limonite cavities and are up to several centimeters long. They are not always covered in green malachite and in some cases occur fresh, bright and copper-colored.

Cuprite is noteworthy, but not very common. Nostiz (JAHR) mentioned two particularly good finds in 1906 and 1909, which yielded numerous pieces with sharp-edged, highly lustrous octahedrons. The deep red translucent to shiny gray-metallic crystals range in size from a few millimeters to over 1 cm. The hair-like, acicular habit known as “chalcotrichite” also occurred, though rarely. Malachite occurs as radial aggregates of acicular-prismatic crystals to several centimeters. In addition, richly studded specimens with centimeter-sized tabular to flaky pyrolusite crystals and beautiful stalactitic “manganomelane” (also referred to as “psilomelane” or “black kidney ore”) are known, which are either amorphous manganese oxide or cryptomelane, or another related manganese oxide. Manganite in small black and highly lustrous crystals is a rarity because this mineral is usually already transformed into pyrolusite. Although it is rather rare to encounter specimens, a variety of lepidocrocite known as “ruby mica”, which consists of druses of fine reddish flakes on limonite, also occurs.

Other mineralogical rarities, which were only discovered in very small crystals and habits, are white chalcoalumite as a pseudomorph after malachite, shiny black delafossite as a companion of cuprite and copper, cerussite (rare crystals up to 1 cm), mimetite, scorodite and pharmacosiderite as well as philipsbornite and corkite (both in similar yellowish, pointed rhombohedral crystals; cf. Golze et al. 2012). All of these secondary minerals occur in limonite cavities, which are commonly lined by botryoidal to reniform goethite. Stalactitic aggregates with a shiny black, some with a colorful iridescent surface, can reach the thickness of an arm and a length of almost half a meter.

Discover more fascinating stories like this?

Mineralica brings you the most fascinating finds, places, and people from the world of mineral collectors – in print and online. A must-have for every collector.

Subscribe now and never miss an issueA mineralogical “trouble maker” is the copper sulphate, chalcanthite, formerly known as “copper vitriol”. Nostiz (JAHR) described it as a blue crystalline coating, shiny reniform aggregates and small stalactites. It occurs on a highly decomposed massive ore with a lot of pyrite. Unfortunately, most of the chalcanthites represented in collections today are likely to be synthetic. Distinctive, sharp-edged crystals, some of which have even been illustrated in textbooks, are often man-made. Wolf Mine is a widely known locality, mainly due to the occurrence of rhodochrosite. Specimens from there are highly sought-after and this unfortunately seems to encourage people to fake or mislabel specimens.