Historical Amethyst Discovery At The Saurüssel

It is not only one of the most important amethyst finds in the Alps, but also an inspiring story: despite adverse weather conditions, Erika and Rudolf Planitzer made a find of the century and recovered beautiful sceptre and sceletal amethysts in the Austrian Ziller Valley

Tyrol’s Ziller Valley branches off from the Inn Valley around 40 kilometers east of the provincial capital of Innsbruck in the Austrian Alps. The valley owes its name to the Ziller river and is surrounded by the Tux, Kitzbühel and Zillertal Alps. The once untouched, beautiful landscape is characterized in many places by mass tourism, which is the region's most important economic sector alongside livestock and dairy farming, and forestry. Historically, the first settlements can be traced back to the Bronze Age (1200 to 800 BC). The earliest documents mentioning the valley are dated 889 AD, when it was owned by the Archbishops of Salzburg. The valley has long been known among collectors for amethyst, iron roses, rock crystal, garnet and diopside - just to name a few of the most important minerals. The Große Mörchner is a 3285-meter high mountain in the Zillertal Alps with imposing cliffs up to 800 m high. It will feature heavily in this article, along with many other important localities. Every alpine collector dreams of having a beautiful amethyst scepter from the Zillertal in their collection. This dream came true decades ago for the Linz-based collector couple Erika and Rudolf Planitzer - and in the form of hundreds of specimens. Matrix specimens, individual crystals and crystal groups fill the shelves of an entire display case and are placed so close together that a leaf can hardly fit between them. What makes it even more exciting is the fact that these are their own finds.

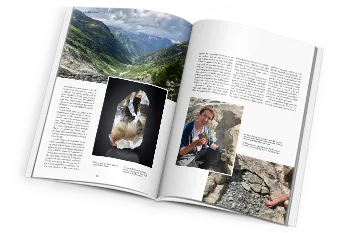

The couple have been interested in minerals for a long time. Rudolf has been interested in minerals since childhood; Erika has been fascinated by botany, mineralogy and geology since her youth. Together they go on collecting trips to Namibia, Tuscany, Germany and the Austrian Alps. For their honeymoon in 1962, the two traveled to the legendary emerald locality in the Habach valley. Six years later, they traveled to the Ziller valley for the first time, where the find of a lifetime was waiting for them. Erika Planitzer provided me with her personal diary for this article. In it, she documents the find described in this article down to the smallest detail. The following excerpts from her diary give an even better idea of the emotions involved in the search. Even after 48 years, her lines, photos and drawings provide an accurate picture not only of the find, but also of the finder's impressions and thoughts. Pioneering for the time, the two had already recognized the importance of precise documentation for science and the interested community in 1976.

The plan was to leave on July 25, 1976. On that day, the Planitzers arrived in the Zillertal, but due to the bad weather, there was already a discussion about calling off the trip. However, the enthusiasm to search for minerals again was very high, so, together with another couple, friends from Linz, they decided to wait out the bad weather. Unfortunately, the following day brought no improvement and it was not until Tuesday, July 27, that the fog lifted and the temperatures rose. The small group climbed up to the Berliner Hütte (hut from the German Alpine Club, Berlin section), but the following day fog and about 10 cm of snow made conditions difficult again. Nevertheless, Erika, Rudolf and their friend Hermann begin their first prospecting on the Saurüssel, which is located next to the Edelweißklamm.

»Found small amethyst splinters and quartz crystals. Maybe we should have another look when the weather is better! - “Suspicious”. On towards Mörchnerkar. At the first Steinmanderl (Cairn marking) already trudged in deep snow. Later in the afternoon, walk back to the hut. Very poor mineral finds, but great, winter landscape.«

Another two days later, the conditions improved and bright sunshine accompanied the trio of collectors on their activities. The year before, Rudolf and Hermann had already discovered a small cleft, which they were able to enlarge and dig deeper into the mountain using long chisels and some effort. Their efforts were rewarded with their first doubly-terminated amethyst. Erika did not work on this cleft, but left the following comment in her diary:

»Did some prospecting between sunbathing and eating, including to the left (down the valley), right next to a big old hole. There was a lot of loose, black biotite here - “like poppies” and some rough, white quartz. I dug a little further and uncovered a small cavity. I didn't say anything yet. Finally fell asleep sitting on my pick at my work site.«

At the end of the day, the finds were shared, the initial success awakened a fascination for new things and motivated the collectors to continue working. The evening ended with a good meal and a few glasses of red wine.

The new premium magazine for mineral collectors

4 issues per year – packed with fascinating finds, expert knowledge, and collector passion. The first bilingual magazine (German/English), including full online access.

Explore subscriptionWhile the two men continued to work on their cleft the next day, Erika devoted herself to her own site. According to her notes, it was 11 am when she asked Rudolf for help with further chiseling work. At first they only came across coarse quartz, but the site began to show more and more interesting signs and soon Hermann joined in. Then the first amethyst-colored crystal surfaces flashed in the sunlight and a funnel-like cavity, completely lined with crystals opened up. Erika's words in her entry still bring the moment to life today:

»I kept picking crystals out of the cleft with my fingers. It was great, incredible and exciting. We unearthed wonderful things. In the evening, everything was laid out and then shared.«

The following day, July 31, there was no holding back and work on the cleft was already in progress in the early morning hours. The cleft sloped steeply downwards and to the right, and more and more finds were made. In the afternoon, Hermann, his wife and son joined the Planitzer couple in their efforts. The mood was excellent thanks to the ever-increasing number of finds. Rain and the cold returned to the high alpine location in early August. The weather conditions prompted Hermann and his family to descend into the valley. In the end, the Planitzers also had no choice but to retreat to the Berliner Hütte, where they spent a day with a good book and some sleep. On August 2nd, there was snow again, and the cold and strong wind were omnipresent. An avalanche even broke loose in the so-called Rutilschlucht (Rutile Canyon). Nevertheless, the Planitzers risked climbing up to the cleft again. Although it was cold and windy, the wild and romantic landscape presented itself in clear air and sunshine. The couple hiked through the wintry scenery completely alone - their only companions were 12 ptarmigans. Erika was struggling with the icy temperatures and the latest she wanted to keep going was until 5 pm. She described her impressions in her diary:

»About half to three quarters of a meter in front of my cleft, a 10 to 12 mm thick quartz vein with slight lateral color changes runs through the rock about 2 m into the depth and disappears into the gneiss. Rudi is magically attracted to it. He begins to clear material away and chisel. Rudi chisels and breaks a narrow passage in the rock and I remove the material. It's almost 3 pm and still nothing, but Rudi continues to work driven by an inner compulsion. And then he breaks out a particularly stubborn, large chunk at the lower end.«

A cavity is now exposed and it took a lot of effort to enlarge. Rudolf, who normally worked at a desk, was not used to the strenuous lifting and soon had to struggle with cramps and pain, but still refused to give up. After Erika had bandaged his forearms, he continued to lift. After considerable work, Erika finally managed to get a hand into the open cleft - here are her words:

»I get to reach in first and pull out a wonderful amethyst, we also call it the gatekeeper as it was right at the entrance to the cleft. I hold it carefully in my hand and can't believe my eyes - it's simply a miracle. So big and beautiful!!! It's hard to believe, but it's true..«

As the hours and daylight dwindled, the two of them once again gave their all to widen the gap even more. They wanted to dig even deeper and find even more treasures hidden in the mountain. The lines in the diary read with a corresponding sense of euphoria and urgency:

»We no longer feel the wind and cold. We carefully bring one amethyst after another into the daylight with pickaxes and scrapers, mainly with our fingers. After many millions of years in darkness, light falls on these incredible, shining wonders of nature for the first time. To be able to experience something like this is a stroke of great luck. I continually say: That's enough now, we can't fit everything in our backpacks. There are some magical pieces in there - and they come out like potatoes and look like potatoes when they're embedded in pocket filling. But there's always a little point or an edge sticking out of the dirt. There's hardly any room left to lay them on, all amethysts. Mainly scepters and often skeletal. You want to share the joy with others and then again you don't. We are blissfully happy. We run out of newspaper when wrapping, because every piece has to be well protected. Everything we have is used as wrapping material - hats, work pants, kerchiefs, toilet paper, tins etc.«

The must-have for everyone who collects minerals

Mineralica is your premium collector’s magazine – made exclusively for lovers of minerals and fossils. In print, bilingual, and with full access to the complete online library.

View issue previewBefore the journey home began, Rudolf cleared more suspicious stones in the pocket, then sealed and camouflaged everything. It was 7 pm before they finally left the site.

»We dragged heavily and carefully, radiant with joy. Maybe that's where the term “STRAHLER” comes from (“strahlen” also means “to radiate” in German).«

They did not want strangers in the hut to notice their find, but the two wanted to share the joy of their find with their friends who had traveled back to Linz. As there were no cell phones in 1976 and Rudolf did not want to tell everyone else in the hut about a large pocket on the phone, he tried to inform his friend Karl about the events in a somewhat cryptic manner. Referring to the name of the location (Saurüssel), he improvised code phrases such as “We pulled a tooth out of the sow”. With the remark “It's our wedding anniversary, friends should come”, he asks for reinforcements. Karl knew how to interpret these sentences correctly and climbed up to the Berliner Hütte with Hermann, Hannes, Gerhard and Otto the very next day. Rudolf had by now realized the enormous dimensions of the find. It was simply too much for one person alone and his best friends should have a share in this find, which to this day is one of the largest amethyst cleft systems in the entire alpine region.

On August 3, Rudolf had already climbed up to the site alone before the first of his friends reached the Berliner Hütte. Erika needed a day to recover and greeted Gerhard, who had driven through the night to travel the long distance to the Ziller valley. After receiving directions from Erika, he climbed up to the site without stopping, finally reaching it at lunchtime. When he arrived, Gerhard only discovered Rudolf's shoes - the rest of his body was already deep in the pocket. Gerhard took a photo of it, which was published in 1977 as the only evidence of the find to date. Even decades later, Rudolf remembers how shocked he was when a pair of legs suddenly appeared in his restricted field of vision. At first he thought another collector might have spotted him and wanted to steal his find, but then he saw the smiling face of his friend, who had come to his assistance. Together they managed to make rapid progress. A considerable number of other good pieces were recovered, safely packed and immediately stowed away in the backpacks. The purpose of this method of working was to prevent hikers or other collectors passing by from guessing the incredible dimensions of the find. In her documentation of the day's finds, Erika mentions not only countless amethysts, but also other special features such as sagenite (lattice-like intergrowth of rutile needles) and tremolite needles as inclusions in the amethysts.

Rudolf and Gerhard discovered water-clear rock crystals on the walls of the chasm, which could not be removed undamaged at this point, so they left them in place for the time being. Erika was able to follow part of the day's work with binoculars, and in the evening she added a report from her husband to her diary:

»Even as they are about to quit, Rudolf pushes himself into the cleft once more and grabs a longish stone from the very back, then passed it back between his legs. Out of the cleft, he wipes the chunk off and it is a flawless, heavily skeletal double-terminated amethyst weighing about 2.62 kg. That was another highlight.«

At around 6:30 pm, Erika hurried from the hut to meet the two men, who were packed with bulging backpacks, a plastic bag filled with more specimens and cameras they were carrying for botanical photography. In the evening, she makes a note in her diary:

»They trudge towards me, marked by the hard, but nice work in the cleft, completely dusty, their faces still covered in pocket debris, bloody fingers, bandages and bruises on their bodies, but beaming with joy. We rest at the Diopsidbacherl (Diopside Creek). I know what they have: no thirst, no hunger (at the moment) - but amethysts. There are huge specimens. About 30 cm long, 15 cm wide, beautifully skeletal, good color. We named a large specimen about 30 cm long with two amethyst sceptres about 16 cm long the “turtle” because of its appearance. The mountain spirits were gracious once again. It was a good day. We get to the hut late. For dinner, as usual, we treat ourselves to a mountaineering menu, a cup of red wine, an omelette or cake. Tastes like nothing before.«

Discover more fascinating stories like this?

Mineralica brings you the most fascinating finds, places, and people from the world of mineral collectors – in print and online. A must-have for every collector.

Subscribe now and never miss an issueOn August 4, the collectors used the day to transport the treasures they had recovered to the Breitlahner parking lot in the valley. The backpacks were heavy - there would be 18 full ones by the end – and they had to take many breaks carrying them down to the valley. Once there, they were repacked as inconspicuously as possible into suitcases, bags and boxes and carefully stowed away in the car trunks. Gerhard, who had to return to Linz for work, was bid farewell before the Planitzers light-footedly climbed back up to the Berliner Hütte with empty backpacks to take two more full ones to the car. The couple also then made their way home - but a return was planned for August 6. They had enough time to clean the items they found before they set off back to the Ziller valley on the morning of August 6th, along with their friend Karl, his wife Heide, Otto, Hermann and Hannes. After the long drive to Tyrol, the starry sky was already shining above their heads when they finally reached the Berliner Hütte at around 10 pm. With high hopes and expectations, the entire group set off the next day to the discovery site. Once again, they were not disappointed. Thanks to the many helping hands, the cleft got bigger and bigger, deeper and deeper and extended deep into the mountain. Amethysts were everywhere. Erika remembers with these lines:

»We hardly take time for a break. We drink soda with water from the Mörchner. The water is clear and pure. Only mineral collectors and sheep drink from it. In the afternoon, two curious collectors visit us and we give them a large block with numerous smaller crystals to break up. They are delighted and moved on happily. The cleft has become so big that three men smeared with clay and dirt are working in it - an experience. The most beautiful specimens keep coming out. Everyone tries to get the foremost and most difficult job - of course, it's the most exciting. I also slip in and lie on my stomach, searching for crystals with my hands - really great. You can still see amethyst crystals shining on the walls of the cleft and the ceiling.«

The work went on until the early evening hours. After splitting up and packing up the cleft was once again camouflaged before the group descended to the hut with seven full backpacks. On August 8, Heide stayed at the hut; Hermann and Karl had to return to Linz. The Planitzer couple and Hannes and Otto remained and continued to work on the cleft. Erika writes in her diary:

»I'm very happy, because I like it so much here in the Saurüssel-Mörchner area that I'd like to spend every day here in summer. At 6.30 pm another hole opens up in the ceiling and we can recover some wonderful pieces. As Otto is the tallest, we build him a pedestal in the cleft from which, supported by us, he can reach more easily and further into the hole in the ceiling, where he feels a loose, thick crystal.«

Only after this crystal had been recovered, did the team finish their work and sealed the pocket for the very last time - over 600 larger crystals, specimens and countless smaller pieces were recovered by the Planitzer couple alone. According to Erika's description, the widely branching glacial streams shone like silver ribbons in the diffuse evening light. A hint of melancholy and the pain of saying goodbye can be seen in her last entry:

»At the Steinmanderl, we see the moon rising over the Mörchner. We lie on our stomachs for a good fifteen minutes and watch as it moves towards the Schwarzensteinsattel, bathing the glaciers, cirques and mountains in a wonderful, mysterious light. For us, it's a great finale to this year's successful tour in the Ziller Valley. We walk slowly and carefully to the hut. One last time for this year.«

When I first asked Rudolf Planitzer in 2011 about the quantity he had found, he stated 18 full backpacks with around 600 specimens. Somewhat shocked, I realize now the incredible scale of the find. He also told me that the display cases, literally bursting at the seams, don't even contain all the pieces, but that there is still a lot of material packed away in boxes and cases in his cellar. Rudolf still had a lot to tell - at that time, the cleft had not even been exploited to its full extent. He never looked for it because of the huge find they already made, but he did visit the area again and again and observed the progress made in the pocket. Over the years, almost nothing remains of the former main pocket. Although it was about 3 m deep, 1 m wide and 2.5 m high when the group closed it in 1976, the rocks around it were almost completely eroded in the decades that followed. Over the years, Rudolf was repeatedly able to discover specimens in collections that could be attributed to his pocket. The total quantity found must therefore be gigantic.

In addition to amethysts, which were found as scepters, negative scepters and skeletal crystals, the following accompanying minerals were also found: smoky quartz, rock crystal, and pyrite (highly lustrous octahedrons up to 6 mm edge length and limonitized cubes up to 15 mm edge length). Rutile was also found as individual crystals up to 26 mm in size on amethyst sceptres or as a sagenite lattices in rock crystal,or even freestanding on host rock. Needle-like tremolite was also found, usually intergrown with rock crystal or amethyst, as well as pericline and chlorite, some of which made for beautiful phantoms. Such large and important finds usually have a considerable financial value, which often reveals the less pleasant side of the human character, but not for the members of the Saurüssel team, who had a deep friendship that lasted for decades and who went on many collecting trips together as far as Namibia. Sadly, two of the participants have already passed away. But the rest of them still meet regularly. This find not only showed great mineralogical quality, but also friendship. Erika and Rudolf Planitzer are now both almost 90 years old and after initial skepticism, they are both very enthusiastic about the idea of sharing this great discovery with a broad community of collectors. After all, Rudolf always wanted to avoid having collectors and dealers willing to buy at his door. Naturally, the news of the find spread quickly and widely - but the two never sold a single piece. Even today, Rudolf still has a story to tell about every little crystal and all the wonderful memories cannot be outweighed by money. Intrusive visitors are shown the door. Erika was, and still is, her husband's unerring nose and expressed a special wish in a personal conversation about this article. She would like to go up the Mörchner one more time - only this time with someone to carry her backpack.

My thanks for this article go to the Planitzers, who so willingly opened their door and show case to me.