Goethe loved Minerals from the Zillertal in Austria

It has long been known that the world-famous poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was a passionate mineral collector. New research has now revealed that he was also interested in the minerals of the Zillertal.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had been Minister for Mining and Road Construction in Duke Karl August's cabinet since 1775, so he inevitably had to seek direct contact with the mining industry. One of his friends, a "vice-mining captain" (in German "Berghauptmann") and later mining captain in Zellerfeld, introduced him to geology and mineralogy. (Maser W.1984) He observed nature and began to collect stones and plants, and in the 1780s he converted his garden house to make room for his mineral collection. In order to acquire knowledge of minerals and rocks, he collected everything that seemed useful to him.

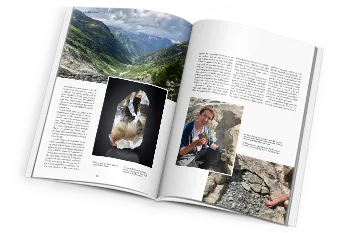

Prescher reported in 1978 that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe not only left behind a large number of literary works, but also an important geoscientific collection of around 23,000 items. Goethe passed through Tyrol in 1786, albeit only on his way to Italy (Italian journey 1786 - 1788) and described the Tyroleans as follows: "The nation is brave, straightforward, the figures are alike." He regretted in his letters that he had no time for the Zillertal and the mines in Schwaz. A comparative examination of the Austrian minerals and rocks in Goethe's collection reveals that the number of specimens from Tyrol is by far the highest. The main area of discovery is the Zillertal, from where almandine, asbestos, cyanite, adular, talcspar, amphibole, diopside, specimens from the gold mine on the Rohrberg etc. are in the collection.

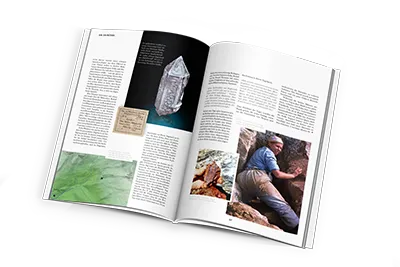

In 2021, Hubert Klausner and Walter Ungerank were allowed to visit the (extremely extensive) mineral collection in Weimar in search of minerals from the Zillertal and further research began.

Between 1784 and 1786, Belsazar Hacquet, a professor of natural history in Lviv, undertook a journey through the northern Alps and described, among other things, the Zillertal Alps, which were popular for their minerals. These books served Goethe as a guide for his mineralogical observations. The recording of mineralogy and the exploration of the geology of the Alps was largely uncharted territory. This is certainly the reason why Goethe was particularly interested in minerals from the Zillertal.

Hacquet reports from his journey through the Noric Alps (1784 - 1786) that "in Breitlahner a hunter offered several square shoe-sized garnet slabs from the Wackseckerkar". He also writes that completely vertical walls are formed there and that mica, garnets and some quartz occur. There is also Strahlschörl on very large slabs. Here he was probably referring to hornblende. He also mentions "the twelve-sided garnets (ruby-colored grains), which are made into jewelry and were recently discovered on the Grawand Alps near the village of Hühnersteig". These garnets were set in shiny snow-white mica and equally colored quartz.

On March 21, 1790, Goethe traveled over the Fernpass and the Mieminger Plateau to Ambras Castle and viewed the famous Ambras collection of Archduke Ferdinand II (1529 - 1595), which was still complete at the castle at the time and was brought to Vienna in 1805/06.

The new premium magazine for mineral collectors

4 issues per year – packed with fascinating finds, expert knowledge, and collector passion. The first bilingual magazine (German/English), including full online access.

Explore subscriptionIn 1817 there was a mineral collector in Innsbruck, Captain von Algener, and a collection of Tyrolean minerals came to Goethe via K. v. Preen from Braunschweig. He acquired three diopside crystals from Zeltenthal under no. 2571-2573.

On 23.8.2021 these specimens were inspected by Klausner and Ungerank and clearly identified as Zillertal diopsides. As these crystals reached Goethe via various dealers, the Zillertal became Zeltenthal.

In 1818, the director of the Court Natural History Cabinet (now the Natural History Museum in Vienna) Carl von Schreibers sent Goethe: garnet in granite, garnets and raystone in chlorite slate, quartz, asbestos, pericline on hornblende rock.

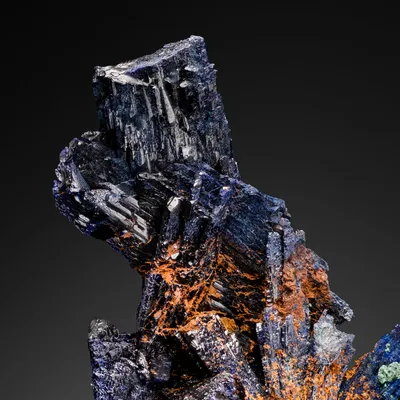

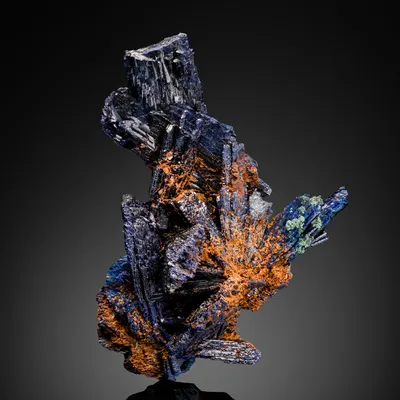

In 1822, Heinrich von Schönau from Zeltenthal sold further diopside crystals to Goethe. Here too, the Schönherr became Schönau and the Zillertal became Zeltenthal. And in December of that year, Grand Duke Carl August presumably gave him another suite of 37 pieces from the whole of the old Tyrol: No. 7377 diopside crystal (large aggregate), 7382 almandine from Tyrol, 7383 garnets from Tyrol (10 pieces unrolled), 7385-7386 almandine garnets from Tyrol, 7388 black tourmaline crystal from Tyrol, 7390 rock crystal from Tyrol, 7391 cyanite from the Zillertal in Tyrol, 7394 asparagus stone from Grainer in the Zillertal, etc.

In 1826, Paul Schönherr found olive-green diopside crystals on the "rothen Wand" (Rotkopf in the Zemmgrund) and sold them in Munich in 1827. Interestingly, the Goethe collection already contained diopsides from 1817, as the first written mention of such crystals is dated 1826. The diopsides in Goethe's collection can be assigned to two different sites on the Rotkopf in the Zemmgrund and in the search for the discoverer of the large diopsides, only Schönherr comes into question.

According to Egg (1990), on June 15, 1826, the Leo national singing group sang in Weimar in front of the poet prince Goethe, who reported the following: "The songs and yodeling of the cheerful Tyroleans pleased our young people. Miss Ulrike and I particularly liked the "Strauss" and "Du, Du liegst mir im Herzen". Goethe dedicated his picture to them with his signature and in 1828 they were back in Weimar. Anton Leo said: "We also sang in Weimar with the famous poet Goethe, whose wife became our friend and gave us recommendations." Goethe said "that he found the popular yodeling only bearable outdoors or in large rooms, and the melody is also arty and naive - I would be able to do the same."

Later, they sang in Prague in front of the former Tyrolean governor "who had tears rolling down his cheeks with joy". In 1830 they were back in Thuringia and Goethe even had Anton Leo drawn by the painter Johann Joseph Schmeller, who painted portraits of the visitors to Goethe's house over the years. In 1831/32 they sang in Düsseldorf, The Hague and in 1833 in England etc.

The must-have for everyone who collects minerals

Mineralica is your premium collector’s magazine – made exclusively for lovers of minerals and fossils. In print, bilingual, and with full access to the complete online library.

View issue previewIn March 1829, mineral dealers from the Zillertal visited Weimar again and also offered Goethe "pretty things" and after consultation with the saltworks director Glenck and Court Councillor Soret (he was the prince's educator), Goethe then bought around 300 Zillertal minerals, such as apatite between adular, cyanite etc. The cyanite (disthen) mentioned here can currently be seen in Ginzling, in the Nature Park House. Goethe was unable to identify some mineral species, and so the castle bailiff in Jena was asked to have a "Tyrolean mineral in columnar form, rough on the inside, quite crystallized on the outside" identified by Mr. Zenker in Jena. The dealers mentioned above were most probably Heinrich Schönherr or Josef Hofer. The badly tumbled garnets and the diopside, which were first found by Paul Schönherr in 1826, serve as possible evidence.

As the Schönherr - Leo - Hofer families maintained good family contacts according to the available documents, it is certain that they also pursued common business interests. The Hofer family owned garnet mines, the Schönherr family traded extensively in minerals (as far as Silesia and Holland) and the Leo family traveled widely in Europe as the best-known "Leonen" family of singers. (Their parents' house was the "Wagner" in Zellbergeben - today between the Huber car dealership and Hotel Engelhof). According to Elsa Schönherr, a Mrs. Schönherr once married a Leo singer.

The Schönherr family was a well-known family of mineral collectors and traders who traveled all over Europe and sold their wares at the court of Amsterdam, among other places. Their mineral wagon is said to still be in the Mineralogical Museum in Munich today. The well-known singing family, the Leo brothers, who also traveled all over Europe and sang at most of the royal courts of the time, had four stores, one each in Hamburg, Kreuznach, Montreux on Lake Geneva and one in Nice. They were initially run according to the season and their children inherited one store each. According to old information, some of these are still owned by their descendants today.

Josef Hofer was a master tailor, traded in honey and schnapps, later in Federweiß (asbestos), which he also sold in barrels to Germany, became a mine owner and traded more and more in minerals, especially garnets. As he was actually a tailor and trader, he probably had no access to explosives. It can therefore be assumed that he registered a business with the former mining authorities in Hall (around 1820 - 1830) as "Privatbergwerk Josef Hofer und Wtw. Schönherr".

This explanation is given because it certainly explains how Josef Hofer was able to build up Europe-wide trade relations in a relatively short time. He received gold medals for exhibitions in Amsterdam, Budapest, Prague etc. and had permanent storage places with forwarding agents in Prague, Rosenheim, Nuremberg etc., often spent months on business trips with his trading partners in Bohemia and Germany and was also mayor of Zell a.Z. from 1851 to 1860.

The Schönherr family were also employed in the mining administration, as evidenced by mine plans from 1855, and Franz Schönherr (1862 - 1928) was still active as a clerk and supervisor in gold mining according to the 1911 survey book and copy book and is mentioned in the Mineralogical Pocket Book of 1911 as a mineralogical guide.

In the "Tags-Blatt für München" of November 25, 1827 it can be read:

The mineral dealer Paul Schönherr, who arrived here yesterday at the Bauhof with a collection of rare minerals, discovered a crystallized mineral of notable quality in 1826 on the high mountains of the southern Ziller valley, on the Rote Wand (today Rotkopf), which resembles the noble emerald in color, transparency and partly also in hardness, and has been given the name diopsite by mineralogists. This is considered to be the first mention of diopside from the red head.

In the Münchner Tagsblatt of 2.12.1831 page 643 you can read:

The mineral dealer Paul Schönherr from the Zillertal has arrived with a new "publishing house" (lot) of minerals, shells etc. and is selling his wares until Dec. 5. He can be found in the building yard at 2 stairs no. 4.

According to this letter, dated Zell on November 8, 1871 to Dr. Daniel Blatz in Heidelberg, he is offered the following minerals with prices: Magnetic iron, precious garnets, diopside, rock crystal, bistazite, mica, brown garnets, blasting stone, fuchsite, tremolite, amethyst, red garnets, apatite, loose garnets and cyanite.

Discover more fascinating stories like this?

Mineralica brings you the most fascinating finds, places, and people from the world of mineral collectors – in print and online. A must-have for every collector.

Subscribe now and never miss an issueHeinrich (II?) Schönherr (year of birth cannot be determined - 1928)

The "Schönherr" probably moved to Zell a.Z. due to the formerly flourishing gold mining industry, which is why this family name does not appear in the registers of Zell. They were probably the brothers Paul and Heinrich. Their place of residence was the former miners' settlement "Kaiserstatt" to the east of Zell. The garnet merchant Josef Hofer (1802-1872) lived about 300 meters away.

In 1889 it is noted in the inventory book of the NHM Vienna under no. G 7673 that Heinrich Schönherr from Zell a.Z. sold a 21x17x8cm diopside (block) with crystal formation of dark green color from the Alpe Schwarzenstein there.

Based on these facts, it can be assumed that Heinrich Schönherr from Zell a.Z. contributed to the fact that so many Zillertal minerals and crystals came to Goethe in Weimar and the many samples of asbestos and garnets could have come from Josef Hofer's collection. The collection of Josef Hofer from Zell a.Z., who manages the estate of his great-great-grandfather Josef Hofer (1802-1872), also contains a small bag of diopside.

The largest diopside crystal, a disthene and tumbled garnets from Goethe's collection are currently on loan from the Goethe National Museum Weimar in Ginzling in the "Hidden Treasures" exhibition.

References

- Büchner, R. (2011): Tiroler Wanderhändler

- Brenner, K. (1964): Der Zillertaler Wanderhandel im 18. U. 19. Jahrhundert

- Egg, E. (1982): Goethe und Tirol, Ausstellungskatalog, Tiroler Landesmuseum Innsbruck, S 3-23

- Egg, E. (1990): Schwazer Bezirksbuch, Inntal – Achental – Zillertal S 225-226

- Hofer, J. div. alte Schriftstücke

- Kahler, M. (1991): Goethes Gartenhaus in Weimar S 3-32

- Prescher, H. (1978): Mineralien und Gesteine aus Österreich in Johann Wolfgang von Goethes Sammlungen zu Weimar. Aus: Bergbauüberlieferungen und Bergbauprobleme in Österreich und seinem Umkreis. Österr. Museum f. Volkskunde S.151-157

- Prescher, H. (1978): Goethes Sammlungen zur Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie Tiroler Landesmuseum, Bibliothek

- Ungerank, W. Archiv u. Bildarchiv

- Unterlagen der Fam. Schönherr: Bilder vom 7.12.2011

- Bilder Goethe Sammlung 23.8.2021 u. 12.6.2023 u. Brenner s. Foto 2020.5.12