A World-Famous Discovery Site: Epidotes of the Knappenwand

The Knappenwand in the Untersulzbachtal in Salzburg has been a world-famous site for minerals like epidote for over a hundred years. Over the years, many different leaseholder have tried their luck and discovered significant finds.

Table of Contents

- The Discovery of the Knappenwand - A Site for Extraordinary Epidotes

- The First Epidote Discovery in 1865

- "...so that the church tower shook!"

- The Vienna Natural History Museum as Leaseholder

- Four Locals Try Their Luck

- February 17, 2004 - A Lucky Day

- The Mining Phase 2006 - 2009

- Clefts Are Rare

- More Clefts and the Big Rockfall

- The Knappenwand from 2015 - 2023

The Discovery of the Knappenwand - A Site for Extraordinary Epidotes

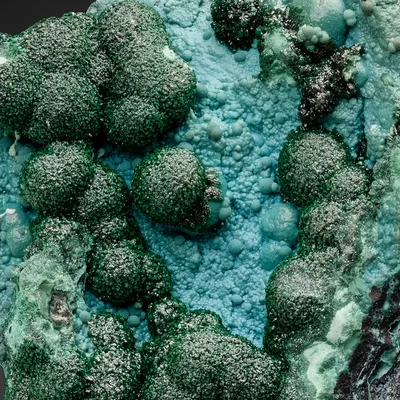

"In the depths inside there was a tangle of rods and sticks, of needles and cones and hair, and it shone and glittered and sparkled and glistened in a splendor never seen before." This is how the legendary priest and local historian Josef Lahnsteiner described the opening of a chasm in the Knappenwand, which he once witnessed.

Looking at some of the finds from the Knappenwand, it quickly becomes clear how apt Lahnsteiner's description is.

In 2019, the Bramberg Museum received a coin from the 18th century from Salzburg mineral collector Karl-Heinz Stauder, which he had found while searching for epidotes below the Knappenwand hut. It can therefore be assumed that in the 18th century (and perhaps even earlier) people were already exploring the present-day epidote site, but probably in search of copper, as the Blauwand tunnels were driven into the mountain just below the epidote site. However, they are connected to the historic copper mine. The mining facilities of the former "Hochfeld" copper mine are located in the fall line below the Knappenwand near the Untersulzbach.

The First Epidote Discovery in 1865

The history of the Knappenwand mineral site begins with Alois Wurnitsch, who came across the amphibolite lens in the front Untersulzbachtal valley in 1865 while looking for minerals. He found stalked, loose epidote crystals, dug around and discovered a cavity with jumbled epidote crystals. He took several of these crystals with him and sold them to his friend, the mineral dealer and master tailor Andreas Bergmann from Innsbruck. He passed the strange mineral on to Prof. Victor Ritter von Zepharovich from the University of Prague, who was able to determine the mineral perfectly and also published a short treatise on it.

This was the beginning of the mining history of the Knappenwand, which can be traced and documented for more than one hundred and fifty years.

After science had recognized the importance of the Knappenwand - because the size, brilliance, color and richness of form of the Untersulzbachtal epidote outshined anything comparable - it also became clear to mineral hunters and mineral dealers what had been discovered here. According to traditional information, Alois Wurnitsch's friend Andreas Bergmann probably began the first exploration work around 1867. The lease agreement that Bergmann concluded with the imperial–royal Forestry Administration was valid for the period from August 1, 1874 to July 21, 1875. The first few weeks of work were unsuccessful and Bergmann already had difficulties raising the wages for the workers, but after the third week success was achieved. And to an extent that even the most optimistic of prospectors could not have expected. The drill suddenly dropped into a cavity. It was impossible not to be amazed, because a large cleft had been opened and the daylight made numerous epidote crystals with lots of byssolite sparkle and glitter.

In 1869, Aristides Brezina, an employee of the imperial–royal Mineralogisches Hof-Cabinet in Vienna, visited the Knappenwand site. He mentioned epidotes up to 13 cm in length in a small treatise. He also speaks of over a thousand exquisite epidote crystals. Such numbers sound unbelievable to our ears, because everyone knows how rare it is to see a good Knappenwand epidote specimen today. Brezina goes on to describe scheelite crystals.

In the first mining period under Andreas Bergmann, the Neukirchen Schwabreit farmer Sebastian Troyer was a diligent and careful worker. Thanks to his careful mining methods, the specimens in the fissures were spared massive vibrations and could therefore usually be recovered without damage. Working in the then still small cave brought Sebastian Troyer a good side income. Bergmann himself was fully occupied with the sale, for which he had to personally visit the major museums and well-known mineral collectors. In 1877 and 1879 there were two auctions, which drove up the rent.

A certain Dr. Edmund Neminar, university professor in Innsbruck, (1.8.1878 - 30.7.1880) appears as the next tenant. As this lease period overlaps with Andrä Bergmann's second lease period (1.8.1879 - 30.7.1881), this confusion could have been caused by the auction procedures.

After the first great successes, mining became increasingly difficult and the mining costs exceeded the proceeds, so that Andreas Bergmann terminated the lease. Nevertheless, the best epidote specimens date from this period. After Bergmann had left the Knappenwand, the Salzburg businessman Carl Steiner took over the epidote site on August 1, 1881 for two years (until July 31, 1883). Nothing is known about his finds. In 1884, a public advertisement for the lease appeared in the Salzburger Volksblatt. It is not known whether anyone dared to undertake the mine-like work. From July 25, 1890 to July 24, 1891, the Hofgastein innkeeper Jakob Viehhauser tried his luck. The enterprising Neukirchen innkeeper Albert Schett was registered as a tenant with three assistants from 1.1.1897 to 31.12.1902. Schett himself was not a stone hunter, but one who set the course for tourism in Neukirchen early on with many activities.

The Bramberg miner Alois Hollaus subsequently (1903 - 1905) worked with an assistant in the Knappenwand. He had a similar experience to Bergmann. Only after a long time without any finds was he successful. The epidote specimen of a large cleft were carried down into the valley in nine humpback baskets, into which hay was filled and the fragile stones packed on top. Alois Steiner Sr. had observed and later recounted how Alois Hollaus, who lived in his neighborhood, had deposited the valuable epidote specimens on the railing of his balcony. He stopped the work in 1905 because, in his opinion, no more lucrative finds were to be expected.

Karl Wurnitsch appears as the next tenant from 1909 to 1913. Peter Troyer, the son of Sebastian Troyer, worked with him. There are even some pictures from this period. Unfortunately, Wurnitsch lost his left eye due to a stone splinter while mining.

"...so that the church tower shook!"

A period of cautious mining was followed by a rather violent mining method with little understanding of the minerals. A man named Nicolussi - who most probably came from Luserna near Trento (Italy) - was not a tenant himself but only an employee. He was probably called Christian Nicolussi, as a document in the archives of the municipality of Neukirchen records this first name. There are three graves in the Luserna cemetery with the name Christian Nicolussi, which also coincide with the worker in the Knappenwand. However, it is impossible to find out anything on the spot about these people and their work abroad, as most of the men from the poor community were looking for work outside their own country at the time and not even their children were interested in where their father earned his money.

And just as he had seen as a railroad construction worker, Nicolussi took a brisk approach. He had 62 boreholes drilled into the hard rock, loaded them with dynamite and enlarged the small quarry into a huge cave with these large blasts. It should have been foreseeable that the sensitive minerals would be severely damaged in this way. Not only were the epidotes in the directly affected area destroyed, the shock waves that propagated in the rock led to the destruction of minerals that were only found decades later. Hermann Unterwurzacher Sr. told the young Karl Podpeskar about the blasting and described it as follows: "When there was blasting in the Knappenwand, the church tower in Neukirchen shook!"

Nevertheless, Nicolussi is said to have found some excellent specimens and brought them to Italy.

After 1922, quieter times returned to the Knappenwand. The Mödling mineral dealer Anton Berger took over the lease in 1929. There are only a few mentions of epidotes in his records, which are still in the family's possession, indicating that the finds were not particularly rich. He was also a correspondent for the Natural History Museum in Vienna, responsible for stone purchases. But Nicolussi's crude methods had destroyed too much. Berger's contract with the Federal Forests ended in 1933. From 1934 to 1935, the minerals expert Hugo Ullhofen took over the Knappenwand.

After the Second World War, Leo Eiter worked at the site from 1946 to 1948. Kajetan Stockmaier and Ehrenreich Schuchter appear as the last tenants, albeit without a lease. The Neukirchen municipal secretary Josef Eiter was also involved. They found all kinds of good epidote spemine. Ehrenreich Schuchter was a blasting foreman and head miner in the Hochfeld copper mine in Untersulzbachtal.

In 1956, the Austrian Federal Forests did not extend the lease for the time being.

The Vienna Natural History Museum as Leaseholder

Stone prospectors repeatedly tried their luck in the Knappenwand, but without a lease (and therefore without permission) no major work could be carried out, so there were hardly any more finds.

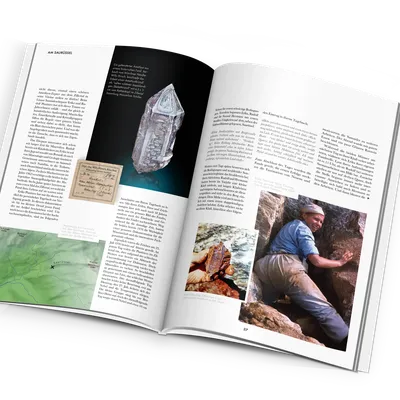

It was not until 1977 that the Natural History Museum Vienna succeeded in obtaining a ten-year lease from the Federal Forestry Office for the "Knappenwand Research Project", after preparatory work had begun in 1973. The head of the project was Dr. Robert Seemann. A new accommodation hut and a transport cable car were built. This time, however, the aim was not to find as many clefts as possible, but to research mineral parageneses, formation conditions, comparative sites, rock sequences, etc. The team from the Natural History Museum nevertheless managed to open 70 clefts.

In 1987, the lease was extended for a further 5 years.

Four Locals Try Their Luck

Since 1992, the Zukunftskollegium Neukirchen has been trying to obtain a lease from the Austrian Federal Forestry Office. This was used to open the "Knappenweg Untersulzbachtal" to the Hochfeld copper show mine and included the Knappenwand as part of it. On January 1, 1998, this contract was extended for a further 10 years and from spring 2001, the Neukirchen rock prospectors Franz Gartner, Josef Brugger and the brothers Gerhard and Hannes Hofer from Wald agreed to move the deposited rock to the side and possibly get back to layers that could also contain epidote clefts.

Since 2002, regular work has been carried out in the Knappenwand again. Dr. Fritz Koller from the University of Vienna was recruited to provide scientific support. The motivated team first began with safety measures on the south-facing wall, from which rock slabs kept breaking out. Only then could the "Knappenwandinger" (= the workers on the Knappenwand) begin to remove the excavated material from earlier times. When they reached the bottom of the large cave, they built a 10 m long tunnel to protect them from falling rocks. Only when it was safe could they start searching for epidote fissures. These were mostly related to the aplite vein at the back of the cave, where clefts often opened up at the points of curvature. Finally, after two years of painstaking preparatory work, they were successful and discovered the first clefts with interesting contents: epidote, byssolite, apatite, calcite, dissolved quartz and albite.

February 17, 2004 - A Lucky Day

Safety is the top priority for all activities on the Knappenwand. The side walls were particularly dangerous, as the rocks were constantly cracking and could fall at any time.

Large sections of rock kept breaking off the south-facing "elm" (side wall) in particular. This was the case again in the summer of 2004, when huge slabs of rock fell onto the portal of the safety tunnel on the valley side. There was a risk of a massive collapse. To protect the team, they extended the safety tunnel by 7 meters "towards the night". Gerhard Hofer then abseiled down the wall in the fall and succeeded in splitting off the crumbling rock sections. The unstable wall was then secured with rock bolts, giving the vaulted ceiling the necessary stability. Mining experts supported the miners with their know-how.

After this securing work was completed, work on the epidote-amphibolite rock could only be resumed in February 2004.

Sepp Brugger Remembers This Memorable Day and Describes the Find

"We had longed for a day like this for a long time. A day that was reminiscent of the great finds at the beginning of the legendary Knappenwand era of Alois Wurnitsch and Andrä Bergmann and yet was completely different. On February 17, 2004, the time had come.

We had laboriously worked our way through an almost numb, approximately 2 m thick epidote-amphibolite stock. The course of the rock in front of us indicated a large fault zone. It was noticeable that rust-red water was leaking from tiny cracks, obviously carrying a lot of dissolved iron oxide. We already knew from earlier that water carrying iron oxide - if it is deposited in cracks - was a sure sign of a fissure. Using wedges, chisels and a small electric hammer, we inched our way closer and closer to the already crumbling rock. And then! Suddenly we saw a 10 cm circular hole in front of us. Each of us could feel the tension. Something was definitely hidden behind it!

When we looked into the cleft, we could see that it did not extend into the mountain (as is usually the case). The cleft ran 15 cm behind the still standing rock bar across the amphibolite rock and we could already see that the back of the cleft was covered with beautiful byssolite up to 3 cm long. Although everyone's pulse was pounding, we couldn't afford to get hectic and now the question arose: which of us would be the first to reach into the cavity? The friends decided selflessly and told me to reach into the cavity. I later realized that this had undoubtedly been a historic moment. I just remember my heart pounding with excitement. I quickly took off my jacket, rolled back the right sleeve of my shirt and carefully ran my fingers through the cold water, feeling my way deeper and deeper into the matted layer of detached byssolite. My fingers came across something smooth, hard and elongated, perhaps even an epidote-like structure? If it really was epidote, then it had to be big, because it weighed quite a lot. Watch out! Watch out! Maximum concentration was required. I felt sharp epidote needles scratching my skin on my arm. Everything was unimportant at that moment, because it was all about retrieving the epidote.

Yes - and then I saw this incredible specimen for the first time in the light of the headlamps and I showed it to my friends standing next to me, curious and in joyful anticipation. We had been working towards such an event for a long time. And now the long-awaited Epidote specimen finally seen the light of day. It was still dirty from the muddy crevasse, but we could already appreciate its dimensions and perfection. The special piece was carefully passed from one hand to the other. Embedded in a prepared box with a soft base, the specimen was then carried to the hut. Of course, we had also prepared a bottle of sparkling wine for the occasion. This had to be used on this anniversary day! We were delighted and let our plant manager Hans Lerch and our scientific supervisor Dr. Friedrich Koller from the University of Vienna know about the find as soon as possible."

The following day, all the rock facing the cleft was removed and the entire size of the cleft was uncovered. Several magnificent epidote specimen came to light and for the first time the Knappenwand had opened up a treasure trove for them, just as Lahnsteiner had described it at the time. A 12 cm calcite, which had once detached itself from the cleft ceiling and from which the rusty brown color of the water had emanated, lay in the middle of the cleft. The completely water-filled cleft - a crack running across the amphibolite rock - had a height of 50 cm, was 40 cm wide and about 10 -15 cm deep. The fissure walls were covered with 1.5 cm to 3 cm long byssolite needles, apatite crystals (up to 0.5 cm) and smaller epidote needles. Based on the amount of water, they estimated the volume of the fissure to be around 20 to 25 liters. Byssolite mud up to 25 cm high (measured from the bottom of the fissure) filled the cavity and at the same time protected the crystals. This mud also contained 3 pieces of loose, 1 cm large diopside, which are rare for the Knappenwand.

There were also several smaller epidote specimens in the mud. The large epidote specimen had originally grown in the upper part of the cleft and had detached a long time ago, but the fracture surface had already healed and the epidote specimen was almost undamaged. The location of the cleft was measured and photographed.

The large epidote specimen is now part of a private collection, but is currently on display in the national park exhibition "Emeralds and Crystals" in the Bramberg Museum, where a series of wonderful epidotes can be seen in a display case.

The Mining Phase 2006 - 2009

The aplite vein, which was clearly visible at the back of the tunnel ridge, has always been a cleft indicator at its bend points. The "Knappenwandinger" Josef Brugger, Hannes and Gerhard Hofer and Franz Gartner therefore followed the course of this aplite vein on the ground and pinned their hopes on it. Other fault zones or special rock folds are also always interesting, as clefts can usually be found in their vicinity. At depth, the vein was up to one meter wide, so the assumption was that new clefts could be found here. However, the exact opposite was the case - no fissures containing epidote were discovered here.

In the following years, a great deal of work had to be invested in securing the side walls, and attention was also paid to possible rockfall hazards from above, as the cavern was already 18 m high. A short tunnel was used to probe to the rear again, but the rock became more and more compact and no clefts were visible at all. Finally, mining began in the direction of the day - again as a drift drive for safety reasons. The level of the tunnel was approximately at the height of the timbered tunnel that had already been built and described earlier, onto which the overburden from earlier times had been piled. The deeper you went, the more difficult it became to load heavy pieces of rock into wheelbarrows and tip them onto the spoil tip. After some deliberation and good advice from reliable helpers, a ropeway was constructed on a cross-tensioned rope to relieve the strain, allowing rubble and rock to be lifted mechanically and transported outside.

A new problem arose - a lot of spring water was seeping out of a crevice in the rock, so that it had to be constantly pumped out. At the same time, an extraction system was installed for the drilling dust, as drilling with water is not possible at sub-zero temperatures in winter.

Overall, the years 2005 to 2007 were relatively unsuccessful in terms of mineral discoveries. Franz Gartner retired from the team in 2007.

Clefts Are Rare

As they were not successful, they stopped driving in the "night" direction, lowered the level and began driving in the "day" direction (2008).Right at the beginning of the tunnel drive (1.30 m lower than the tunnel level of the old tunnel), they observed a thin calcite vein (4 cm wide), which they were able to follow for about 4 meters. The miners had already noticed an interesting phenomenon several times. Whenever red-colored - i.e. ferrous - harness surfaces appeared, there was almost certainly a cleft nearby. It was the same here. Several pocket-like clefts filled with small epidotes, byssolite and calcite were found in the immediate vicinity of the calcite vein. They cleft again and found more fissures. In a bulging area, they came across a long but narrow cleft whose walls were lined with fine, long-fibered byssolite. In the cleft itself lay disc-shaped calcite, in which the imprint of a large epidote was visible. The epidote itself had detached from the calcite, lay loose in the cleft, is 12 x 2 x 4 cm thick and has sharp-edged and highly lustrous head surfaces. The reward after several weak years! Further beautiful epidote specimens, associated with long byssolite hairs, were brought to light. Rock crystals, apatite, calcite, albite and small sphenes were also among the finds.

After completing the fissure work, a drill was used to probe in the direction of the day and it was soon realized that the rock pillar was only very thin up to the day and therefore did not allow any further mining. So the thin layer was left standing. A new tunnel was excavated from the outside a few meters below, in front of which a small hut was built in late autumn 2009.

More Clefts and the Big Rockfall

In January 2010, a devastating rockfall, which originated in a side channel above the Knappenwand, fell over the Knappenwand. Even the huts of the Hochfeld show mine far below the site were affected. Fortunately, no one was on site that day. This event brought a lot of extra work for the Knappenwand staff. The path to the Knappenwand had been devastated and then had to be made rockfall-proof. Protected by an overhanging rock, the tunnels and buildings were largely spared from the landslide. During the landslide, a huge tree crashed head first into the ground just in front of the Knappenwand hut, the tangle of roots with stones and earth damaged the roof of the hut and destroyed the toilet facilities. Part of the lower-lying equipment hut was also torn away and the goods road to Untersulzbachtal was closed for the whole summer and had to be renewed. Although a stone wall now protects the goods road, it is not advisable to stay in this area, as falling rocks are always present and it is almost impossible to avoid the stones that shoot down this steep slope.

Josef Brugger, a deserving "Knappenwandinger" from the very beginning, retired from the work in 2011 for reasons of age. Since then, brothers Hannes and Gerhard Hofer have been working alone.

After 2012, there were some clefts that revealed magnificent epidotes up to 16 cm long. In the following years, the brothers Gerhard and Hannes Hofer worked and searched diligently, but there was hardly any success. You have to have a great deal of stamina to get through this hard work without even the smallest cleft appearing.

The rockfall that had fallen over the Knappenwand in 2010 had calmed down and the protective measures had been completed, so that you could climb up to the site and stay there without feeling uneasy, even if you can never tell whether large boulders might come loose.

It is impossible to mine upwards towards the ceiling of the large cave in the Knappenwand, so a drive was made at a lower level in the hope that clefts would appear in the deep green amphibolite. No matter how good it looked here, no clefts were encountered, not even small ones.

As the weather was bad in 2014 anyway, meaning that it was not possible to search for stones at higher altitudes, the Hofer brothers decided to go to the Untersulzbachtal valley at least two to three times a week to dig for the epidotes. At the same time, they repeatedly had to work on the renovation of the house in Wald im Pinzgau.

In the months from May to July, the brothers were again following the promising-looking, hard green rock when they finally came across a fist-sized calcite outcrop close to the ground. They knew from experience that they had to be very careful here, as something like this could well be a fissure indicator. In fact, after a few blows with hammer and chisel, the matter was clear, as the calcite vein gave way and a small cavity opened up.

Water collected at the bottom of the fissure. The surrounding rock was carefully removed and the fissure gradually revealed its secrets. In the center was a freely crystallized calcite, which did not look very spectacular. In addition, there were small but bizarre epidote formations (up to 7 cm long) - often associated with byssolite. Small, white albites also appeared. This football-sized cleft was the culmination of two years of hard work. Further narrow fissure slits were subsequently found more often, so that in the end a certain number of pretty epidote-byssolite specimens could be found.

The Knappenwand from 2015 - 2023

In the following year, 2015, there were no successes despite great efforts, and the brothers invested their manpower elsewhere, so that the Knappenwand went quiet for the time being. Although the "Zukunftskollegium Nationalpark Hohe Tauern" continued to operate the Hochfeld show mine, it terminated the lease agreement with the Austrian Federal Forests in 2016. The Hofer brothers now managed to lease the Knappenwand on their own. They then drilled boreholes into the hard amphibolite at close intervals from the lowest point and added a pipe camera, which would have allowed them to detect small changes or even clefts. But it was jinxed - not a single cavity was approached or discovered in this way. This reduced their motivation and in the following years their activities were limited to maintenance work on the hut, the path and the tunnels.

Whether and how things will continue at the Knappenwand cannot yet be predicted exactly. In any case, epidotes from this magnificent site are and will remain a rarity, as new finds will continue to be very rare in the future, if they are found at all.

Many thanks to Christian Hager for providing the mineral photographs.

References

- Burgsteiner, E.: Kristallschätze – Mineraliensucher im Oberpinzgau, Bode Verlag, Haltern, 2002;

- Burgsteiner, E.: Mineralogische Neuigkeiten aus dem Land Salzburg, Bode-Verlag GmbH, Haltern, 2004;

- Burgsteiner, E.: Mineralogische Neuigkeiten aus dem Land Salzburg, Bode-Verlag GmbH, Haltern, 2005;

- Burgsteiner, E.: Salzburg - Land einzigartiger Mineralien, Bode-Verlag GmbH, Salzhemmendorf, 2010;

- Burgsteiner, E.: Mineralogische Neuigkeiten aus dem Land Salzburg, Bode-Verlag GmbH, Salzhemmendorf, 2013;

- Burgsteiner, E.: Mineralogische Neuigkeiten aus dem Land Salzburg, Christian-Weise- Verlag, München, 2015;

- Burgsteiner, E.: Mineralogische Neuigkeiten aus dem Land Salzburg, Christian-Weise- Verlag, München, 2005;

- Lahnsteiner, J.: Oberpinzgau – Von Krimml bis Kaprun, Salzburger Druckerei und Verlag, Hollersbach, 1965;

- Lerch, H., Lewandowski, K., Zukunftskollegium Nationalpark Hohe Tauern: Bergbau im Untersulzbachtal – Eine fast vergessene Welt, Eigenverlag, Neukirchen, 2006;

- Seemann, R.: Epidotfundstelle Knappenwand, Verlag Doris Bode, Haltern, 1985;